Music

at an Exhibition:

The 1889 World's Fair in Paris

Annegret Fauser

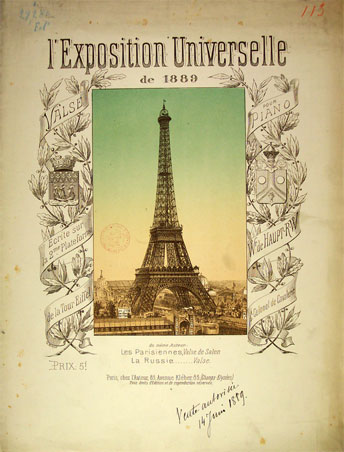

Title page of L'Exposition Universelle (Paris 1889), a collection of short piano pieces, Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris

|

Music

at an Exhibition: Annegret Fauser

|

Title page of L'Exposition Universelle (Paris 1889), a collection of short piano pieces, Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris |

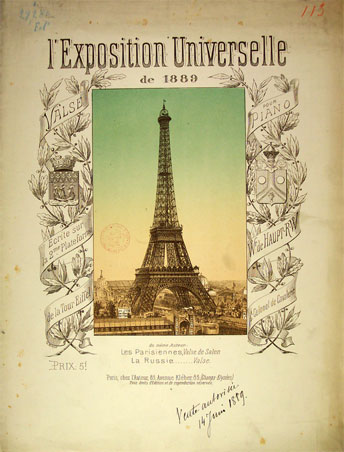

The 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris has become famous as a turning-point in the history of French, if not Western, "modern" music. For the first time, Debussy and his fellow composers could be inspired by Javanese gamelan music, while the Russian concerts conducted by Rimsky-Korsakov brought recent music by the Mighty Five to Parisian ears with works such as Mussorgsky's Noc' na lysoj gore (Night on a Bare Mountain). But the 1889 exhibition had much wider ramifications for music and culture in France. Musical performances and political aspirations at this World's Fair contributed to the patriotic and colonialist projects of a nation, which was at the point of breaking out of its international isolation to join new European political alliances while reviving its economy after two decades of decline. More than any other French World's Fair, the 1889 Exposition Universelle was also defined through its political context, given the fact that it celebrated the centenary of the French Revolution through an event, which aimed to be—in the words of the 1889 Guide bleu—a "gigantic encyclopaedia, in which nothing was forgotten." Indeed, it was one of the most successful World's Fairs in history. More than 30 million people came to visit a site, which extended over almost a square mile on the Champ de Mars, and where visitors could admire the displays of 61,722 exhibitors.

Music was so pervasive at the 1889 Exposition Universelle that newspaper journalists described the sonic side of the affair as a "musical orgy." Sounds reached from bandstand marches to symphony concerts, from Javanese gamelan music to telephonically transmitted operas. Indeed sound enveloped visitors from the moment they entered the Fair to the second they left, and comments about this sonic landscape permeate the rich literature reflecting their reactions and responses, from newspaper column to memoirs.

Concerts formed a regular exhibit of art music from both France and foreign countries as showcases for national achievement in music. In addition to the five official orchestra concerts organized by the official committee headed by Ambroise Thomas, organ concerts and early-music performances contributed to display the richness of French musical heritage to the visitors. Foreign orchestras and choirs from countries such as Russia, the USA, Finland, Norway, Belgium and Spain were also present.

At the Fair itself, operas were visible only in the exhibition of French theater and audible only by transmission in the telephone pavilion. However, the evenings at both Opéra and Opéra Comique turned into Exposition events extra muros. The great première at the Opéra Comique, Jules Massenet's Esclarmonde, in particular was treated as the musical pendant to the Eiffel tower, while the retrospective of revolutionary opéras comiques such as Grétry's Raoul Sire de Créqui was originally to be performed at the Fair itself. Furthermore, programming and special events at the Opéra shed a different light on cultural consumption in Exhibition Paris.

Given that the 1889 Exposition Universelle represented also the commemoration the centenary of the French revolution in 1789, political music played a prominent role. On 11 September 1889, in the biggest covered space available, the centenary celebrations of the French Revolution reached their climax with the presentation of Augusta Holmès's Ode triomphale en l'honneur du centenaire de la révolution de 1789. Holmès's large-scale composition and its reception offer a classical case study for the way in which political, personal, and artistic agendas can collude and collide in such a major celebratory event.

Exotic music—whether from Java or Rumania—on the one hand, and music technology (the exhibiting of Edison's gramophone and telephonic opera transmissions) on the other appear as two sides of the coin in terms of visitors' encounter with unfamiliar sounds. While the so-called primitive music was tied to the natural, even animal world, technologically originated sounds were invested with supernatural qualities. In both cases, however, Western listening attitudes were challenged by sounds that burst open traditional horizons of expectation with respect to what was perceived as music. In particular Julien Tiersot's and Louis Benedictus's musical responses to these unfamiliar sounds reflect both contemporary concerns with mediation and the first steps in the fledgling discipline of Comparative Musicology.

In my book, a close examination of the way, in which music was used, appropriated, exhibited, listened to and written about during the six months of the Exposition Universelle allows a unique approach—through the means of thick description and micro-history—both to the role of music in France during the 1880s and, more generally, to the mechanisms of the socio-political uses of music in late-nineteenth-century Europe. I approach music at the Exposition Universelle with respect to its artistic and social contexts, its musical and literary contents (where appropriate), its presentation within the framework of the Exposition Universelle, its reception in France and abroad, and its impact on musical politics and discourses. Through the exploration of a micro-historical approach within the field of musicology, this book will also contribute to the current methodological debates in musicology by showing through a specific example what kind of interdisciplinary approaches may (or may not) be successful strategies for musicological research.

Although World's Fairs in general, and the role of music within them in particular, have attracted some scholarly interest, the approach to music at the 1889 Exposition Universelle has remained almost exclusively either through the lens of its impact on Debussy or linked to the development of specific national musics such that of Spain or the USA. Recently, Jane F. Fulcher (1999) devoted part of a book-length study to the 1900 Exposition Universelle, in particular because of the interface between the political constellations created by the Dreyfus Affair and musical appropriations within the event. Fifteen years ago (1989), the 1889 Exposition Universelle received some attention with Pascal Ory's monograph, L'Expo universelle, analyzing the event in its political, social and cultural aspects, and with various exhibition catalogues (in particular, that of the Musée d'Orsay, 1889: La Tour Eiffel et l'Exposition Universelle). But, as is the case with many such cross-disciplinary enterprises, both Ory and the contributors to the catalogues said almost nothing about music.

A book which brings together a range of music-oriented perspectives on the 1889 Exhibition will offer a new and exciting approach to musical culture in late nineteenth-century France, with respect not only Western art music but also to popular and non-Western music, and to new technology. Such a book could show the way in which musics of different contexts were received in late-nineteenth-century Europe, how both the general public and French musicians reacted to the different musical exhibition "pieces," and how the new disciplines of musicology and ethnomusicology drew important impulses from the event.

Chapter Outline with Subtitles

Introduction: The Politics of Sound

PART 1: SONIC IDENTITIES OF FRANCE

Chapter 1: Concerts and Competitions at the Exposition Universelle

Chapter 2: Images of the Nation? Opera and the Politics of Identity

Chapter 3: The Republic's Muse: Augusta Holmès' Ode triomphale

PART 2: VOICES FROM OTHER WORLDS

Chapter 4: French Encounters with the Far East

Chapter 5: Belly-Dancers, Gypsies and French Peasants

Chapter 6: The Uncanniness of Technology: Listening to Telephone and Gramophone

Conclusion: Music, Culture and Identity

Appendices and Bibliography

Some Texts and Images From Part 2: Voices from Other Worlds

1. The Music of Other Peoples

A. Other Musics at the Exposition Universelle

Rome is no longer in Rome; Cairo no longer in Egypt and Java no longer in the East Indies. All has come to the Champs de Mars, on the Esplanade des Invalides and the Trocadéro. Thus, without leaving Paris, we have the leisure to study for the next six months at least their exterior manifestations, the uses and customs of the most distant people. And since music is one of the most striking manifestations of them all, none of the exotic visitors of the Exhibition will be able to forget it. Without speaking of the large concerts of orchestral music, vocal music and organ music which were just opened at the Trocadéro, we find, in the various sections of the Exposition Universelle, much occasion to study the different musical forms specific to those races who understand art in a very different fashion from ours; and even when these forms should be considered by us as characterising an inferior art, we nevertheless have to pay attention to them, because they show us new aspects of music and are probably infinitely closer to the origins of our art that, today, is so complex and refined.

Julien Tiersot,

"Promenades musicales à l'Exposition," Le Ménestrel, 26 May 1889, 165-6,

at p. 165

B. Nineteenth-Century Anthropological and Ethnographic Views of Non-European Musics

The history of music is inseparable from the appreciation of the special abilities of the races that have cultivated it. This, in essence ideal, art only exists through man who creates it and whom nature gave nothing but sound and time. Under whatever aspect one might examine the musical productions spread over this world, from the most rudimentary song to the most grandiose and complex works, one can only notice it as the product of human abilities which are distributed unequally among peoples as among individuals."

François-Joseph Fétis: Histoire générale de la musique depuis les temps les plus anciens jusqu'à nos jours, 6 vols. (Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1869-76), vol 1, i

The inhabitants of Europe and those of the colonies founded by them have, in general, the necessary aptitude to seize the tonal relationship between certain tone series. This aptitude is developed through the habit of listening to music, which is perfected by study, because the law of progress is inherent in the nature of this race. Through it, they possess the ability to sing in tune and to vary the forms of their song.

Fétis: Histoire générale, vol. 1, 12

As I have said earlier, the creation of the true art of music was limited to the white race, a mission that could not have been fulfilled by black and yellow races.

Fétis: Histoire générale, vol. 1, 119

Towards the end of his life, in 1867, Fétis presented a study, "On a New Form of Classification of Human Races According to Their Musical Systems" (Sur un nouveau mode de classification des races humaines d'après leurs systèmes musicaux), to the Société d'Anthropologie on the close relationship between anthropology and musicology which received the support of Broca during the subsequent debate

The main aim of this book is to facilitate the study of oriental music—far too neglected thus far—to people from the Occident. […] We encourage strongly the musician-archeologists who are attracted by this kind of studies to translate the greatest number of oriental song (both religious and secular) into European notation. They would be rendering a tremendous service to both science and art.

Louis-Albert Bourgault-Ducoudray: Etudes sur la Musique ecclésiastique grecque: mission musicale en Grèce et en Orient, janvier-mai 1875 (Paris : Librairie Hachette, 1877), vii

All the divisions and subdivisions in the taxonomy of human races that one has tried to establish so laboriously will not invalidate the fact that all men, without exception, possess the same senses and that the sense of hearing has given them that of sound; as for the results, they can only be related to the degree of culture and civilization that one can observe here and there.

Félix Clément: Histoire de la Musique depuis les temps anciens jusqu'à nos jours (Paris: Librairies Hachette et Cie, 1885), 3

2. The Exotic Exhibition during the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1889.

"This Fair has no reality: it is almost as if one were walking in the set of an Oriental play…"

Edmond and Jules de Goncourt: Journal: Mémoires de la vie littéraire, ed. by Robert Ricatte, 3 vols (Paris: Robert Laffont, 1989), vol. 3, 271

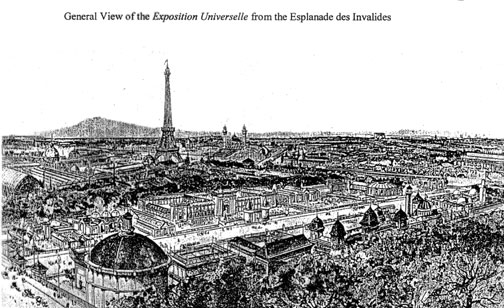

3. Encounters with the Danseuses javanaises

|

"Come to the Javanese village, the Kampong, with me. There, four very young women, dressed up like goddesses, dance a symbolic ballet accompanied by the sounds of the gamelan." Balthasar Claes: "Chronique Parisienne: La Musique à l'Exposition," Le Guide musical, 9 Jun 1889, 3-4, at p. 3 |

|

Engraving of Javanese Dancers, in L'Exposition Universelle, 1889, Supplément no 27 (Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris) |

Painters and musicians are the most fervent. Every day, one can see dessinateurs and aquarellists who use [the dancers] as models during the representation. As for the musicians, they are struck by the unfamiliar rhythms and bizarre sonorities of the two orchestras, which play in the background and on one of the sides of the stage. "Echos de Paris," L'Evénement, 27 Aug 1889, 1

|

4. The Sound of Javanese Music

"Do you not remember the Javanese music able to express every nuance of meaning, even unmentionable shades, and which make our tonic and dominant seem like empty phantoms for the use of unwise infants. Try no more to place before us poor old 'mi, la, re, do' of an ancient and doubtful nobility."

Claude Debussy's letter to the poet Pierre Louÿs of January 22, 1895:

Javanese music is based on a type of couterpoint by comparison with which that of Palestrina is child's play. And if we listen without European prejudice to the charm of their percussion , we must confess that our percussion is like primitive noises at a country fair.

Claude Debussy on Javanese music in an article written in 1913

Whisperings, murmurs, the rustling of a tree the wind, raindrops … nothing but the sounds of nature, and inconceivable melody.

Judith Gautier, "Les danseuses javanaises," Le Rappel, 27 May 1889 / 8 Prairial an 97, 1

Players of the Javanese Anklung during the Exposition Universelle.

Illustration from the weekly illustrated journal L'Illustration.

5. The Musical Theater of Vietnam

L'archi-comble de l'archi-exotisme, c'est de se plaire au Théâtre Annamite, c'est d'ouïr, sans broncher, durant de longues heures, les extraordinaires miaulements de l'acteur principal.

Emile Goudeau: "Théâtres de l'Exposition," La Revue illustrée, 4 (1889), vol 2, 171-74, 171

Actors of the Vietnamese Theater (Photograph of 1889; Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris) |

Claude Debussy's Description of the Théâtre Annamite in 1913: In Vietnamese theatre, one performs a kind of embryonic music drama which is influenced by the Chinese and where one recognizes the formula of the Ring; only there are more gods and less scenery. A raging small clarinet guides the emotion; a Tam-tam organizes the terror… that is all! No more specially constructed theatre, no more hidden orchestra. Claude Debussy: Monsieur Croche et autres écrits, édition complète de son œuvre critique avec une introduction et des notes par François Lesure (Paris: Gallimard, 1971), 223-4 |

6. Parisian Reactions to the Music of Vietnam

|

Then began a deplorable emulation between [the actors] and the musicians. It is a fight: the former try hard to dominate the brouhaha in screaming, with exasperated contortions, like animals in the process of being slaughtered, while the latter furiously double their effort on their tam-tam and on their zebra-skins stretched to the point of ripping apart. The result is an infernal racket. Hippolyte Lemaire: "Théâtres," Le Monde illustré, 15 Jun 1889, 398-99, 399 And what music! The most discordant charivari of lunatic amateurs would seem like a celestial harmony after this. Heavy strokes on a piece of wood or on pots; a kind of flute whose sound enters your ear like a rotary drill. It is music for torturers, made to accompany the agony of prisoners whom one has forced sharp reeds under the fingernails, or whose head was put into a hermetically sealed cage that contains a rat—a pretty rat with pointed teeth in order to nibble on your lips, your nose, your eyes, slowly and with pauses… Jules Lemaitre: "Le Théâtre Annamite," Le Figaro, 8 Jul 1889, 1 |

Performance of "Le Roi de Duong", Engraving of the Théâtre annamite, in L'Exposition Universelle, 1889, Supplément no 21 (Bibliothèque Historique de la Ville de Paris) |

7. Reaction to the Reactions

Western prejudice in matters artistic has seldom been illustrated more strongly than in an article which appears in our Belgian contemporary, "Le Guide Musical", upon the music of the Annamite Theatre, which is so singular a feature of the Paris Exhibition. It is not necessary to quote from the article, but it may be said that it is written throughout in an unsympathetic vein which is surely ill-chosen, in dealing with a subject of such interest to all students of comparative musical science. The critic discovers only horrible discordant noises and relics of musical barbarism, in the art thus illustrated. We shall not go so far as to declare that to the ears trained to appreciate the modern music of Europe, much satisfaction is to be derived from these primitive performances; but the adoption of the tone indicated is scarcely to be commended. It displays a complete inability to alter the critical standpoint, or to depolarise habitual convictions – two things which must be accomplished by anyone who undertakes to assess these performances at their true value. What, it may be wondered, would the Annamites themselves think of a Beethoven symphony?

Unsigned article [C. R. Day?]: "Facts and comments," The Musical World, 69 (1889), 409. Date of the issue: 29 Jun 1889.

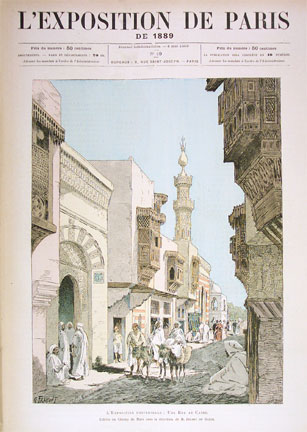

8. Oriental Dance at the Rue du Caire

G. Traiponi: La Rue du Caire, engraving published on the title page of L'Exposition de Paris, 4 May 1889 (BHVP). Traiponi's rendered the scene with a strong focus on the exotic architectural detail and the picturesque Arabs in the front, while the European visitors of the Exposition Universelle disappear in the background and are barely visible. |

Judith Gautier: "L'orient: almées, ghaziyés, derviches, rakkasas, danseuses noires," Le Rappel, 29 June 1889 - 11 Messidor an 97, 1-2, 1

"Curiosités de l'Exposition: Les Concerts Africains," Le Petit Journal, 10 July 1889, 1 |

… Let us embark across the sea… The podium is long and covered in carpet: right at the back are the musicians and in front of them the almées … The small stage and the hall are roofed by an awning which is held up by the trees that have been left from the Champ de Mars… The ganoûm, oud, darbouka, resound under the fingers of the musicians… The almées Adila, Farida, Hanem Mohamed, Kadra appear one after the other on the front of the stage in their iridescent costumes.

Adolphe Aderer: "La Musique à l'Exposition," L'Exposition de Paris, vol. 2, 286-87, 287

|

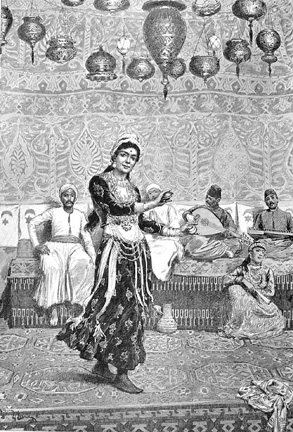

[The belly dance which could be] found just everywhere, in the cafés of the rue du Caire, in the Tunisian market, on the Esplanade des Invalides and which seems to have bewitched the Parisians and hypnotized the fair-goers. Arthur Pougin: Le Théâtre à l'Exposition Universelle de 1889: Notes et descriptions, histoires et souvenirs (Paris : Librarie Fischbacher, 1890), 102 Those who dream to a certain extent, who have fabricated for themselves an ideal Orient through the conventional lens of artists, are really disappointed. Hey what! Is this the dance of the Egyptians? Could it be such rude spectacles that the potentates of the crescent-moon relish in the secrecy of their harem? . . . How far from the least oriental ballet in the Opera, how vulgar, how unlike the descriptions of writers or the striking images of the painters are these obscene calls of girls moving rhythmically to a barbaric motive, the precise opposite of those accents which our Western musical language applies to express the infinite voluptuousness of the flesh. . . Ibrahim: "A l'Exposition: La Danse du ventre," La Vie parisienne, 27 (1889), 333

|

Adrien Marie: "La Danse de l'almée Aïoucha au café égyptien de la rue du Caire," Le Monde illustré, 3 Aug 1889, 73 |

9. Egyptian Musicians and Dancers

Three of the dancers of the Concert égyptien. |

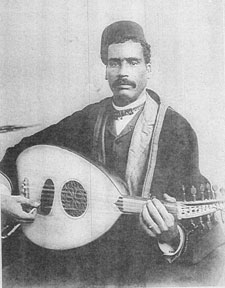

Omar-Hellal, 25 years old, musician from Cairo. Ethnographic photograph from the collection of Prince Roland Bonaparte, collection of the Société de Géographie, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Départment de Cartes et Plans, We 341 (8): 2e Concert égyptien. |

Osman-Hassem, 26 years old, musician from Cairo. Ethnographic photograph from the collection of Prince Roland Bonaparte, collection of the Société de Géographie, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Départment de Cartes et Plans, We 341 (9): 2e Concert égyptien. |

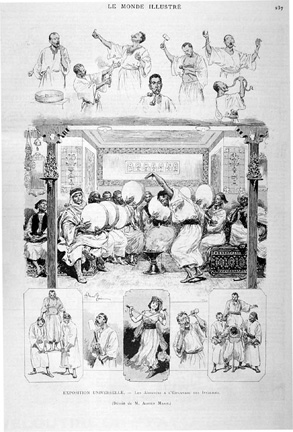

10. The Aissaoua

Adrien Marie: "Exposition Universelle. - Les Aïssaouas à l'Explanade des Invalides," Le Monde illustré, 12 Oct 1889, 237 |

Music here plays the role in which we see it appear in most ancient and classic legends. Its magic power exercises itself fully, and almost as much over the nerves of the spectators than those of the main character. The power lies much more in the rhythmic accent than the form; truth be told, the violent and agitated interpretation is actually the essential ingredient. Is it not through analogous manifestations that in the primitive times music originally revealed itself? If one considers closely the fables of Linus, Orpheus or Amphion, does it not seem as if music as it was conceived of in legendary eras had an analogous nature to the one that was just examined. Later, the pure and learned forms of the art made us forget or disdain these rudimentary formulas: but while their charm is greater, is their effect on the human spirit not less? Julien Tiersot: "Promenades musicales à l'Exposition," Le Ménestrel, 1889, 309

|

11. Music Technology at the 1889 World's Fair

The 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris offered exciting and often surprising aural pleasures. Military bands serenaded passers-by from the bandstands; musical couleur locale was provided in the Romanian or Moroccan taverns; never-before-heard sounds from foreign cultures accompanied the spectacles of African village life, Vietnamese theatre or Javanese dance. But strangest of all were the familiar melodies of French opera heard through acoustic tubes. Indeed, the Pavillon des téléphones with its opera transmissions by phone, and the exhibition of Edison's phonographs were amongst the greatest attractions of the exhibition. They proved to be places of magic and discovery, but also of uncomfortable awe, however much tamed within the secure parameters of an industrial fair. To go and listen to sounds that had no immediate source was to catch a glimpse of a future which might well bring with it some if not all of those strange and wonderful inventions which had become so popular in novels by Jules Verne. The prospect was at the same time enticing and frightening.

A. Imagining the Electronic Transmission of Music:

Morin: 'Transmission du son. - Auditions théâtrales à distance', Le Monde illustré, numero spécial exclusivement consacré à l'Exposition de l'Elecricité, 22 Oct 1881, p. 12.

In the top-left corner, the source of sound, two small figures on the stage of the Opéra, produce the stream of notes—I assume one system per singer rather than a piano reduction. This stream penetrates the walls of the Palais des Champs-Elysées to be channelled into the acoustic tube that leads to the ear of an excited female listener. As one commentator wrote: "It is for sure that every person who hears for the first time a telephone is struck by surprise; this mysterious voice, which comes from so far, has something strange."

B. Reactions to the Sound

Louis d'Hurcourt: 'Téléphones et phonographes à l'exposition universelle', L'Illustration, 19 Oct 1889, p. 328

We have been told that the 'auditions théâtrales' by telephone, organised by the Société [Générale du Téléphone], were one of the great successes of the Exposition. When the occasion offers itself to us to judge de… auditu, we follow the crowd of visitors and enter the rooms reserved for the auditions from the Opéra Comique. We see that Massenet's Esclarmonde is on the programme. We put the receivers on our ears, and we perceive at once, with incredible clarity, the voices of the singers, the slightest modulations of the orchestra, of which one can distinguish, as a matter of speaking, each instrument. We recognise the voice of Miss Sanderson who finishes a phrase with a high C, of which we lose not a single vibration and which is followed by a round of applause; if one closes one's eyes, one would believe oneself to be in the theatre itself of the Opéra Comique. One of the listeners, whom the illusion has caught, puts down his receivers in order to applaud; - the laughs of his neighbours bring him back to reality. After the Opéra Comique, it is the turn of the Opéra, which we hear with the same clarity [in the room next door]; none of the harmonic effects of La Tempête escapes us; - at moments, when the orchestra plays piano, we hear the steps of the ballerinas.

Nemo; 'Le Théâtre par Téléphone à l'Exposition', Le Figaro, 2 July 1889, p. 2